The Acropolis in Athens went through many disasters. After its construction in the form we know it today in the 5th century BC, it became the object of vandalism of fanatical Christian priests in the early Christian centuries, suffered from numerous natural disasters, was periodically burned by invaders, was turned into a gunpowder depot during the Ottoman Empire. In 1822, the temple officially was passed to the hands of the Greek state and proclaimed a monument by the first Greek King Otto of Bavaria. All additional buildings having nothing to do with its original purpose were destroyed and restoration works began.

The first attempts of the New Greek state to return the Parthenon sculptures, brought by the British diplomat Lord Elgin and sold to the British Museum for 35 000 pounds sterling, date back to that period. These attempts became a permanent priority of the Greek state for more than two centuries and reached their height when the famous actress Melina Mercouri became Minister of Culture of the Mediterranean country.

Endowed with their emotional temperament, generations of Greek intellectuals, diplomats, scholars, journalists and ordinary citizens will condemn Lord Elgin’s sacrilege, who removed dozens of bas-reliefs and statues from the ancient Greek temple in 1801-1802 with the special permission of the Sultan and transported them to Britain. Even today, they can be seen in the halls of the British Museum in London.

"I do not want to sound like a defender of Lord Elgin, but we must admit he was a product of his time. For centuries, wealthy British noblemen had taken tours mostly in Italy but also in Greece to seek antiques and brought them to Britain to save them from vandals. At that time, there was not Greek state - it was only a province of the Ottoman Empire. Lord Elgin as Ambassador requested and received permission from the Sultan to remove and take these sculptures with him," recalls Nikolaos Karapidakis, director of the Greek state archives. The historian believes that Lord Elgin had feared that French diplomats were preparing an even greater "rescue" operation for the sculptures and bas-reliefs from the Parthenon. "The reluctance of the British Museum to return these sculptures is another evidence of the importance of the Athenian Acropolis. Even if stolen, they continue to send its message," concluded Nikolaos Karapidakis.

Initially,

the publishers had the idea to give the collection to any official

guests attending the opening of the Acropolis Museum. But realizing the

idea was late. The ambition of the scientists was the edition to

resemble the original documents as much as possible, but it was

difficult. Photographer architect Velisarios Voutsas took up with the

task. He applied the method of facsimile reproduction and using a system

of complex lenses, a professional camera and a computer was able to

zoom the image so that all the details on the documents could be

described. Defects of the paper, deleted cross outs, occasional dust,

damage. Seventeen different paper and ink specifications have been

described. The most difficult was to find such a paper and a printing

press in order to obtain, using modern equipment, the same image as the

one made more than 170 years ago. Thanks to Velisarios Voutsas patience

and professionalism, the obtained similarity with the original documents

is 98%.

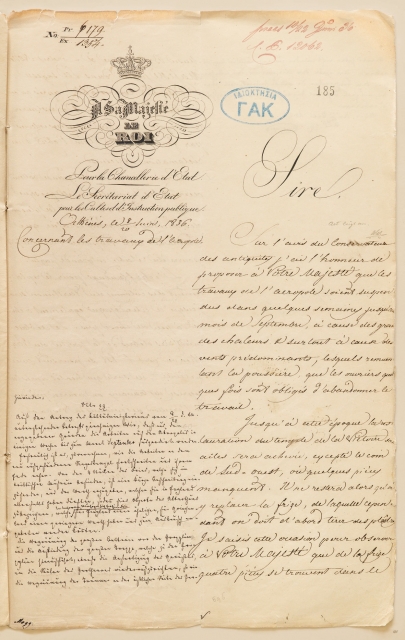

Initially,

the publishers had the idea to give the collection to any official

guests attending the opening of the Acropolis Museum. But realizing the

idea was late. The ambition of the scientists was the edition to

resemble the original documents as much as possible, but it was

difficult. Photographer architect Velisarios Voutsas took up with the

task. He applied the method of facsimile reproduction and using a system

of complex lenses, a professional camera and a computer was able to

zoom the image so that all the details on the documents could be

described. Defects of the paper, deleted cross outs, occasional dust,

damage. Seventeen different paper and ink specifications have been

described. The most difficult was to find such a paper and a printing

press in order to obtain, using modern equipment, the same image as the

one made more than 170 years ago. Thanks to Velisarios Voutsas patience

and professionalism, the obtained similarity with the original documents

is 98%."The documents are interesting not only for historians but also for ordinary people and the similarities with the present time are really startling," says the director of the Acropolis Museum Dimitrios Pandermalis. The collection reveals that immediately after the Acropolis was proclaimed a monument, six persons were appointed as guards. One of them went on leave immediately and the other five immediately began to protest that there was a lot of work. The government was forced to cut the opening hours of the Acropolis. Then, the guards began to complain that their remuneration was very low. Today, their claims sound quite familiar.

Dimitrios Pandermalis has devoted much of his life to the returning of the sculptures stolen by Lord Elgin and the Acropolis Museum was built so that there is a place for them. Today, plaster copies are placed instead of the original sculptures, which are at the British Museum. "We argued whether to put plaster copies in the place of the stolen works or not to put anything. Emptiness sends a very strong message, but in its present form, the museum calls for collecting the sculptures," he recalls.

Thanks to the sponsorship of Postal Bank, the luxurious collection of the documents is present in each public library - whether municipal or school. And the authors of the edition do not regret the delay. "At a time when the Acropolis became a symbol of our bankrupt country, these documents come just in time to show us once again its intrinsic value to human civilization," concludes the editor of the edition Nikos Hadzigeorgiou.

No comments:

Post a Comment